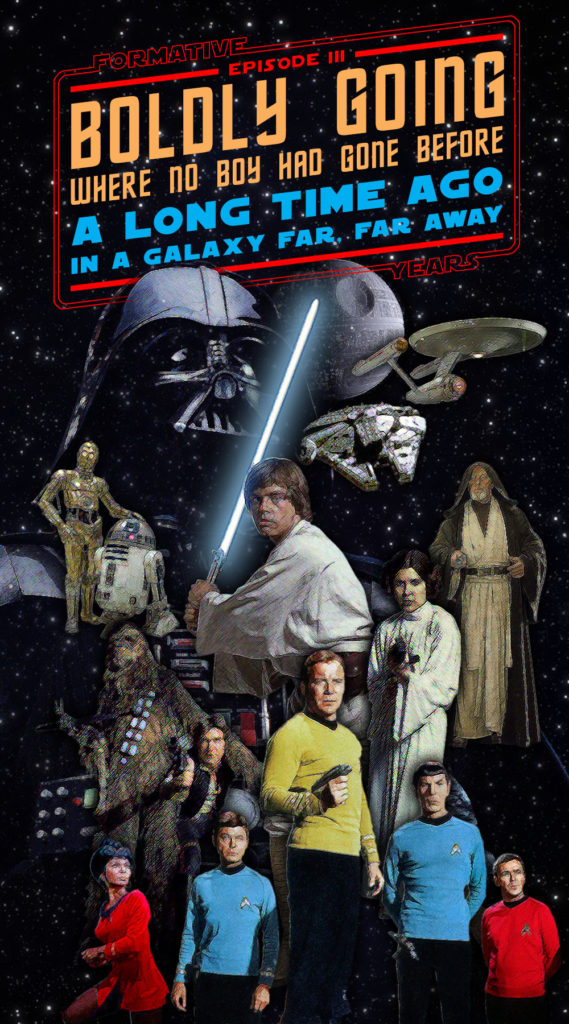

THE FORMATIVE YEARS PART III: Horror, fantasy, and science fiction in the ’70s

The 1970s were a renaissance period of sorts for horror, fantasy, and science fiction. Magic, the macabre, and a pervasive fear of the future seeped out of virtually every pore of public consciousness. What a great time to be a kid! I may not have fully understood the awe-inspiring sounds and images emanating from the television at the time, or that they were often conveyances for more meaningful meditations on society, but they had an indelible impact.

THE CYCLICAL NATURE OF INFLUENCES

In the era before home video and cable became common conveniences, media consumption was a different game. As such, my knowledge of the greater world was largely confined to printed works, records, radio, and whatever programming our standard “rabbit ears” could draw into the family television set. But this wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. The dearth of outlets for contemporary productions meant that I basically absorbed 50 years of Hollywood output by age eight. Because of those experiences and the fact that I’ve existed long enough now to have, at least, twice observed revivals of the pop culture phenomena of my youth, I understand the cyclical nature of influence.

For example, in rock music, a line of influence can be traced from ’70s post punk rock through to the new wave revivals of the last few decades. It works the same way in visual arts, regardless of medium. To that point, creatives in the 1970s were clearly inspired by the horror/fantasy/sci-fi works of the generations that preceded them.

VAMPIRES & WEREWOLVES & BIG LIZARDS IN MY BACKYARD, OH MY!

The ’70s were an amazing time for any kid who had an (unhealthy) interest in movie monsters. Small, medium, and large; bitey, hairy, and fighty; stompy, flighty, and swimmy… There really was something for all tastes.

UNIVERSAL CLASSIC MONSTERS

Even now, I recall the influence Universal’s Classic black & white monster films (1925-1956) exerted on American culture in the 1970s. The studio’s legacy of definitive archetypes (Frankenstein; Dracula; Wolf Man) was everywhere. It was evident in the music on the radio (“Monster Mash,” “Werewolves of London,” “Frankenstein“). Variations on their monster designs were utilized in the TV shows I watched (The Munsters; Monster Squad; Hilarious House of Frightenstein) and films I was, perhaps, too young to see (Young Frankenstein). Universal’s properties were leveraged to sell toys and sugary kids cereals. For crying out loud, Boris Karloff (Frankenstein; The Mummy) even lent his voice to the beloved 1966 holiday cartoon How the Grinch Stole Christmas!

In the Detroit area, the black and white Universal movies aired on Sir Graves Ghastly‘s Saturday afternoon “creature feature.” Looking back, each series began well enough – faithfully honoring the spirit, if not the plotting, of their source material. Further, making use of light and shadow, rather than blood and guts, the filmmakers effectively provoked scares from castle settings and inventive creature designs. Unfortunately, in time, each series diluted to the point of self-parody after long successions of forced sequels. Really, though…who cares? Quality control? What’s that? I was a little boy. As far as I was concerned, the more monsters they could shoehorn into a single movie the better (House of Frankenstein, Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein). If they’d just presented 90 glorious, lightning-filled minutes of monsters cage-fighting in medieval laboratories, that’d been perfect.

THE STUDIO THAT DRIPPED BLOOD

Eventually* I discovered Hammer Studios’ comparatively gruesome, cleavage-filled, color updates of Universal’s monster paradigms (Horror of Dracula; Curse of Frankenstein). Produced over a span of three decades (’50s – ’70s), the film series from “The Studio That Dripped Blood” roughly paralleled the creative paths of Universal’s properties – each starting respectably only to collapse under the weight of overnumerous, ill-conceived and exploitative low-budget sequels. In contrast to their predecessors, however, Hammer made frequent use of classically trained actors and period-appropriate gothic settings. More often than not, the movies starred Christopher Lee & Peter Cushing – known to other nerddoms, respectively, as Sarumon the White and Grand Mof Tarkin.

* Unbeknownst to Mom, who would not have approved.

MONSTERS ARE SUPERHEROES TOO?

In the world of comics, a relaxing of the Comics Code Authority* spurred an explosion of horror comic books. I was only vaguely aware of this development at the time, but all the publishers went all-in. Marvel dropped “superheroes from the crypt” (Morbius; Werewolf By Night; Dracula; Ghost Rider; Frankenstein’s Monster) directly into their established continuity. When Marvel introduced Man-Thing (Savage Tales #1), DC predictably answered with Swamp Thing (House of Secrets #92) a mere 2 months later (“WHAT?!!! They developed a SWAMP monster?!? PREPOSTEROUS! RIDICULOUS! OUTRAGEOUS! We MUST have one!!!”).

* An arch-conservative concern that had been neutering content and imaginations since 1954.

THEY MIGHT BE GIANT MONSTERS

Giant monsters were also very much in-style in the ’70s. Locally, the original black & white King Kong (1933) and Godzilla (1954) films were televised on Saturday afternoon horror blocks. Fun, kid friendly Japanese import giant super-monster slugfests from the ’60s & ’70s (color Godzilla movies; Ultraman; Johnny Socko and His Flying Robot) ran on weekday afternoons.

In 1976, King Kong returned in a meh update starring Jeff Bridges that traded the original’s once state-of-the-art stop-motion photography for a green-screened dude in a laughably unconvincing gorilla costume. If only the creature effects were the worst of it’s problems… Long-story-short, the De Laurentis‘ paid top dollar for a b-movie that creeped-out audiences everywhere with its pervy, bestial fetishizing of leading lady Jessica Lange.

Anyway, taken altogether, these shows were a big influence. In my hands, all 4-color pens were an excuse to transform into Ultraman. At pools, rivers, and beaches, when not role-playing the classic Marvel superhero Sub-Mariner (“IMPERIOUS REX!”), I imagined myself as Godzilla; rising from the sea to smash buildings, stomp cars, and do mighty battle with other freaky gigantors.

SCREEN HORROR EVOLVES

Film updates to classic monster tropes persisted throughout the ’70s (Dr. Jeckyll and Sister Hyde; Blacula; Frankenstein: A True Story), but horror appetites had evolved and expanded.

Exploiting the insecurities of a disillusioned populace, American movie studios brought forth disaster films by the gross. Unlike conventional horror/suspense films – where the terrors are derived from the evil that man do and/or supernatural sources, the disaster genre plays on people’s deeply-rooted fears of the reasonably plausible. In place of the bitey undead, the antagonists were burning buildings (The Towering Inferno) and sinking ships (The Poseidon Adventure). Instead of Mummys and invisible men, audiences were plagued by aeronautical mishaps (Airport) and, well, plagues (The Andromeda Strain).

Supernatural threats still abound, though. Vampires and mad scientists never go out of vogue. It’s just that the standard monster tropes (vampires; werewolves; mad scientists) had given a lot of ground to gory demonic possessions (The Exorcist), damaged telekinetic prom queens (Carrie), mutant-huge sharks (Jaws), slasher flicks (Halloween), zombies (Dawn of the Dead), pod people (Invasion of the Body Snatchers)and acid-bleeding bugs from outer space (Alien).

SOMETIMES A FANTASY

Although my personal exposure to swords, sorcery, and the occult was limited, interesting developments were afoot all around.

My earliest impressions of the fantasy genre came by way ’60s reruns; from TV shows like the Munsters, Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, Addams Family, and H.R.Pufnstuf. Disney’s kid-friendly fantasy films (Pete’s Dragon; Escape to Witch Mountain) played occasionally on Sunday evenings. And, of course, I watched monster movies as often as I could. At some point, works based on author J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth grounded series entered the house… I remember the “fotonovel” for Ralph Bakshi‘s 1978 Lord of the Rings movie. Right around that same time, my oldest sister received a book of Brothers Hildebrandt paintings. Principally collected from Tolkien calendars (’76-’78), the book also featured Greg Hildebrandt’s disturbing cover artwork from Black Sabbath’s Mob Rules, as well as his poster design for Star Wars. I was intrigued, to say the least.

SWORDS AND SCORCERERS

Outside my purview, in 1970, Marvel comics began a long run of Roy Thomas-penned Conan comics. Most famously drawn by comic legends Barry Windsor-Smith and “Big” John Buscema, these books (Conan the Barbarian; Savage Tales; Savage Sword of Conan), along with the works of Frank Frazetta & Boris Vallejo, helped establish the visual language for the swords & sorcery genre as a whole going forward.

As I alluded to earlier, J.R.R. Tolkien’s writings found wider audiences via animated mainstream adaptations of The Hobbit (Rankin/Bass) and The Lord of the Rings. Additionally, Tolkien lore wielded great influence in the realm of hard rock music; evident via explicit lyrical references in songs by Led Zeppelin (“Ramble On“; “Misty Mountain Hop“) and Rush (“Rivendell“; “The Necromancer“), among others.

ROCK STARS ARE (NERDY) PEOPLE TOO

On the whole, a vast number of well-known and emerging rock acts expressed the influence of decidedly non-pop music themes. Some (Led Zeppelin; Black Sabbath; Yes; Hawkwind) composed songs steeped in mythic fantasy tradition. Others gravitated toward horror (Misfits; Blue Öyster Cult; Cramps; Bauhaus) and science fiction (Rush; ELP; David Bowie; B-52’s). Alice Cooper, Talking Heads, XTC, and Devo sometimes utilized the imagery provoked by fantasy genres to disguise biting social commentary.

And then we have the absurdist glam-funk heroes Parliament (“Dr. Funkenstein“) and Richard Elfman’s surrealist Mystic Knights of Oingo Boingo*. Composed of massive orchestra-like lineups, each group approached fantasy themes though elaborate presentations that bore more resemblance to gothic musical theater than rock and roll. Sadly, I didn’t discover George Clinton/ Parliament-Funkadelic until Red Hot Chili Peppers provided the gateway in the late-’80s. There is a chance, however, that I might have seen the Mystic Knights when they appeared on The Gong Show.

*The pre-fame incarnation of brother Danny Elfman’s Oingo Boingo.

CONCEPTUAL (YOU’RE SO)*

Any cursory examination of 20th century science fiction reveals that all was not well with the world. “Life imitates art” just as art imitates life. Onscreen, while it’s certainly true that most sci-fi adaptations aberrated from their literary sources (Frankenstein; The Time Machine; The Island of Doctor Moreau; I Am Legend: The Sentinel), themes relating to the conflicted nature of humanity – it’s impressive native adaptability vs. it’s inherent self-destructive arrogance – remained central.

* Sorry (I’m not sorry) for the obscure references, folks. This is a play on the name of the Adam & The Ants song “Physical (You’re So).” A few years later they released a track called “Picasso Visita el Planeta de los Simios.” I couldn’t resist.

** Good to see some things never change, eh?

INTO THE ATOM AGE

After observing the conceptually light, fun early space explorer-adventurer serials of the ’30s and ’40s (Buck Rogers; Flash Gordon), it’s hard to miss the pattern of xenophobia that enveloped virtually all sci-fi productions post World War II. The ruination of Hiroshima and Nagasaki laid bare the potentially calamitous power of nuclear energy. The atomic age had dawned, wiping away virtually all sanguine curiosity regarding science, technology, and the unknown among the general populace. Everyone feared nuclear energy, but few outside of the scientific community truly understood the systems behind it. So, when ignorant creatives innocently used implausible science as plot devices, the gaping holes in logic usually went unnoticed by the general public.

ENTER THE MARVEL AGE

One benign example of this is the manner by which different forms of radiation were misrepresented in order to provide the foundation for Stan “The Man” Lee‘s Marvel Age of comics (est. 1962). Marvel superheroes were (are) my favorite, but the “science” that bred them is, of course, complete b.s. Lee needed plot conveniences to quickly explain away hero origins and allow stories to cut straight to the action. Therefore, “cosmic rays,” gamma bombs, and radioactive spiders were respectively applied as the source of the Fantastic Four‘s, Hulk‘s, and Spider-Man‘s powers. His readers didn’t know any better, so why not, right?

BAR BARB-ARELLA

In film, however, radiation and the “unknown” were almost universally panned as something to be feared, period. By the 1950s, sci-fi had mostly degenerated into a funereal dirge of joyless space-horror flicks (War of the Worlds; Forbidden Planet; The Thing; The Blob; This Island Earth), botched experiments (The Fly; Tarantula), and irradiated giant monsters (Godzilla; Them!). And then, on the other hand, was 1968’s Barbarella, starring “Hanoi Jane” Fonda. Campy, dumb, and exploitative to it’s core, at least this infamous B-grade space epic provided a much needed reprieve from the wasteland of unpleasant futures that dominated ’70s cinema (THX1130, Silent Running; Logan’s Run; Zardoz).

MOSES VS. THE PLANET OF THE APES

Known mainly to modern audiences through several 21st century attempts by 20th Century Fox* to again cash-in on once lucrative properties, no sci-fi downers that crossed my path in the ’70s had a greater cultural impact than the original Planet of the Apes series.

Spawned from the 1963 French novel, La Planète des singes, the Apes films were a catch-all buffet of depressing themes common to sci-fi media of the day… Disillusionment toward authority/societal institutions (Longest Yard; Outlaw Josey Wales; Three Days of the Condor)? Check! Fear of dystopian futures (Deathrace 2000; Mad Max)? Check!! Well intentioned technology gone wrong (Westworld; Embryo)? Check!!! Kicking things off, the first Planet of the Apes, like so many movies from dystopian sci-fi’s heyday (The Omega Man; Soylent Green), starred Moses from The Ten Commandments. Four similarly high-reaching sequels followed in the early ’70s, chased by a TV show, a Mego toy line, and 1975’s Return to the Planet of the Apes cartoon.

TALKING APES ARE COOL

Depicting a future where lower-primates have evolved to supplant humanity as the alpha inhabitants of Earth, the first movies effectively play as contemplative morality tales. Put aside the base fears at the heart of Planet of the Apes‘ commercial appeal. Pay no mind to the convoluted continuity issues that resulted from stringing the series along a little too far. Sci-fi was merely a vehicle for posing challenging questions about race, inequality, human rights, animal rights, fear, hubris, fascism, war, etc.

I wasn’t even five when first exposed to the Apes series by way of ABC Detroit 7’s weekday afternoon movie, so the deeper subtexts were probably beyond me. No, at that age, the space capsules and talking apes were cool enough. It’s very much like the way ’70s kids voluntarily suffered any amount of lame human drama from Six Million Dollar Man Bionic Bigfoot in order to catch even the briefest glimpses of Bionic Bigfoot.

* Since swallowed up by the Disney entertainment cabal.

THE LIGHTER SIDE OF SCI FI

Luckily, the state of sci-fi during that span of time wasn’t a complete bummer. To kids of a certain age, all the doom and gloom paled in comparison to the allure of cool-looking ships, groovy spacesuits, talking robots, nasty beasties, mighty battle, and high adventure.

Because of the newness of the TV medium, execs from the first few decades of American broadcast television were much more prone to roll the dice on truly imaginative content than those operating today. Risks tended toward light fantasy… Sitcoms (Mr. Ed; My Favorite Martian; I Dream of Jeannie), aquatic adventures (Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea); and westerns (Wild Wild West). But execs also, on occasion, gave harder-hitting, conceptual science fiction anthologies a chance (The Twilight Zone; The Outer Limits). 1966’s Dark Shadows gave vampires a run at the afternoon soap.

1950s American TV revivals of Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers once again stimulated a interest in the space explorer/adventurer category. England’s BBC followed in the ’60s with Fireball XL5 (filmed in “Supermarionation“) and Doctor Who (’63-’89). My two favorite sci-fi shows, however, were reruns of the classic Swiss Family Robinson reinterpretation – Lost In Space (“Danger Will Robinson!“) and Gene Roddenberry‘s fantastically influential and enduring leap into the “final frontier,” Star Trek.

STAR TREKKIN’

When the original Star Trek ended in 1969, few seriously expected that it’d be a major cultural force after ten years, let alone 60? Cancelled after just three seasons, the show amassed a formidable following in the ’70s via syndication. Taking a loose survey of Star Trek’s legacy in the present day, I found that it has sired, to date, no fewer than nine further television series, thirteen feature films, a Saturday morning cartoon, and endless parodies.

BEAM ME UP, SCOTTY!

Everyone in my family loved Star Trek except for Dad, of course (“I have imagination…when it makes sense!). The program appealed to youthful imaginations through its use of vibrant color palettes, cool ship designs, nifty and gadgets. Beautiful matte paintings depicting “strange new worlds” were a highlight of every episode. Compelling stories challenged viewers to grow beyond binary notions of right/wrong and good/evil. Stagey (over)acting entertained and exciting music and sound effects accompanied all actions. Above all other considerations, Star Trek taught me about the perks of being a space captain and the norms for responding to potential conflict (HA!).

Whatever I was doing, inside or out, I found a way to land in front of the TV console every weekend evening to watch the voyages of the Starship Enterprise. Trek battle music played in my head when playing outside. Whenever in sufficiently rugged-looking terrain,* I was looking to engage in mortal combat with a Gorn warrior (“Time…to hit…the sides of his…head…with dual…CUPPED HANDS!”). I coveted my brother’s AMT model Enterprise and younger cousin’s Mego dolls. Along with Batman and Bugs Bunny cartoons, it was surely my favorite show. And then…

* Literally, any setting.

MY FIRST STEP INTO A LARGER WORLD

The late ’70s were a dark time for cinemagoers. The evil leaders of corporate media had audiences caged in a relentless, dispiriting cycle of oppressive dystopian futures. Fear had proven profitable. …But all was not lost. Raised in the “Indie” wilds, young rebel director George Lucas emerged to blindside the American film industry with his world-changing, escapist homage to the pure space adventurer serials of yesterday – Star Wars. Not “Episode IV.” Not “A New Hope.” Just…Star Wars.

SURPRISE SUCCESSES

Star Wars debuted on Wednesday, May 25, 1977 to much acclaim. Simply hoping for modest returns on their $10 million investment, and completely oblivious to the fact that they’d produced, arguably, the most influential pop culture phenomena of the late twentieth century, a pessimistic 20th Century Fox opened Star Wars in limited release (32 screens) across the U.S. Much to their surprise, the movie caught fire immediately and, by August, has spread to over a thousand theaters domestically. By the end of ’78, global ticket sales exceeded an unprecedented $400 million (over 1.3 Billion in 2021 U.S. dollars).

Tangentially, later that year, Steven Spielberg’s warm, refreshingly non-fatalistic tale of first contact with alien species – Close Encounters of the Third Kind – was also welcomed by rave reviews and keen public reception.

WHY ALL THE SURPRISED FACES?

Did the studios have sound reason for grossly miscalculating the connection Star Wars and Close Encounters would make with audiences? In hindsight, as a casual observer/enthusiast, I believe their myopic view was more attributable to a general industry-wide distaste for the genre than anything else. Yes, Sci-fi projects were expensive to make but they were profitable. Stanley Kubrick’s much lauded 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) may have initially failed to recoup production costs for MGM, but redeemed itself famously through re-releases starting in ’71. Syndicated episodes of Paramount’s Star Trek TV show were extremely popular throughout the ’70s. FOX’s own Planet of the Apes property did well enough to justify continued exploitation well into the mid-’70s. Obviously, they should have known that there was an audience for epic space stories.

STARFIELD MEMORIES

Despite the profound influence Star Wars had on my kid brain, I’d only just turned 5 during the first few months of its original run and, as such, can’t recall the experience of seeing it in the theaters at that time. Did we see it as a family? Which theater? Nearly forty-five years down the road, none of us can remember. Details regarding my indoctrination to the ways of the force notwithstanding, the movie stuck with me.

Standing atop of the mountain of outstanding visuals and sounds that made an immediate impression, I recall the striking flow of 20th Century Fox’s fanfare into the main title music-title crawl-opening space battle… The Millennium Falcon immediately displaced the Enterprise as the coolest spacecraft ever to appear on any sized screen. The final space battle and subsequent destruction of the Death Star were unlike anything that had ever been presented on film! …LIGHTSABERS!!!

Are my earliest memories real or illusory? Are they genuine or simply the result of constant reinforcement courtesy of the Lucasfilm merchandising machine and innumerable repeat viewings? All that matters is that I was very excited and moved by the experience, which, at best guess, occurred some time before the summer of ’78 – around the time Star Wars stuff began infiltrating the home.

GIVE YOURSELF TO THE POWER OF THE STAR WARS

My full surrender to the ways of the Force wasn’t immediate. Superheroes had held a singular place in my young psyche practically since birth, so turning me was no small feat. Doing so required unrelenting waves of media saturation, family/peer influence, and Star Wars product.

Every actor and character involved in the production became overnight celebrities. Memorable quotes from the movie became part of the standard banter at school (“May the Force be with you“; “Great kid! Don’t get cocky“; “I have a bad feeling about this“). At home, I perused pictures in the novelization while listening to the soundtrack record. My brother – a promising illustrator/draftsman in his youth -meticulously recreated ships and famous scenes (Vader vs. Obi Wan lightsaber duel v.1.0) in vivid charcoal/pencil drawings, and model kits (Millennium Falcon, X-Wing, Darth Vader’s Tie-Fighter).

Retail stores were packed with t-shirts, trading cards, comics, handheld electronic games and toys. Kenner’s exponentially expanding toy lines commandeered large expanses of shelf space in department stores. Meco’s disco adaptation of the theme music played on the radio.

On TV, movie and toy promos aired constantly and cast frequently appeared on talk shows. Networks aired tribute variety shows. In 1978, CBS broadcast the infamous Star Wars Holiday Special. Highlighted by a cartoon segment that introduced the popular bounty hunter Boba Fett, the otherwise abominable program was immediately disowned by all at Lucasfilm and repressed in collective memory until YouTube came along.

ALONG COMES KENNER

Many major toy companies, failing to recognize Star Wars‘ commercial potential, passed on the toy license until Kenner lucked into it. Initial rollout was rough, though. Due to the lateness of the agreement, failure to anticipate demand, and Lucas’ reluctance to offer reference images ahead of the film’s release, no toys were available for Christmas ’77. Oops! Regardless, sales soared once products began to hit the market in ’78 – exceeding $100 million annually in ’78 and ’79.

Inarguably, Kenner’s greatest innovation was the popularization of 3.75″ action figures. Prior to Star Wars, the only small-scale figures I recall accompanied Fisher Price/Richard Scary playsets and my brother’s Space: 1999 Spaceship. More portable and affordable than 8″ (Mego) and 12″ (G.I. Joe) dolls, the smaller figures also more easily accommodated sets and vehicles that matched their scale; making them more optimal for active play and ease of storage.

SEDUCED BY THE POWER OF THE FORCE

My personal mania for collecting Star Wars items started slowly; escalating precipitously as more items found their way into my possession. The very first Star Wars toy to come home may have been the large-size Darth Vader figure. Stray items followed here and there (Escape From Death Star board game; a Play-Doh action set), but Christmas ’78 was the clincher.

My parents didn’t habitually spoil their kids with “stuff” year-round, but always made up for it for birthdays and Christmas. That said, I awoke Christmas morning in 1978 to find a treasure trove of Kenner Star Wars merchandise under the tree… Santa left a Millennium Falcon filled with about 3/4 of all figures available at the time. A large Obi-Wan Kenobi was presented to provide a sparring partner for my large Darth Vader. Supplementary reading material was offered in the form the Star Wars Storybook. That was it. I was hooked.

From then on, all I (mostly) wanted for Christmas, birthdays, and everything in-between, was more Star Wars swag. I joined the official fan club and read the Bantha Tracks newsletter. Luke Skywalker supplanted Batman, Spider-Man and Captain Kirk as my go-to live-action role-play option. I practiced drawing by sketching freehand studies from figures and trading cards. Between toys, cards, patches, posters, books, and comics, by the time Kenner phased out the original trilogy line in ’85, I’d amassed an impressive collection. I knew kids who had even more, but it was pretty ridiculous.

RUINS

Sadly (hanging head), today, only a few meager artifacts remain of my once proud collection. Some items were sold (many annoyed grunts); some handed-down to younger cousins (many more annoyed grunts). But hey! On the plus side, thanks to comic shows and the internet, I get to gaze longingly at the tragic ruins of other people’s broken Star Wars collections along with Hasbro’s overpriced reproductions.* Awesome.

* That I can’t afford to buy and wouldn’t have space to display even if I could.

THE LONG SHADOW OF THE FORCE

Star Wars‘ cultural presence was constant leading into the 1980 sequel The Empire Strikes Back. Between the original film’s first, lengthy theatrical run, yearly re-releases, advertising, and the regular release of fresh merch, the property never had a chance to fade.

Even as the studios, desperate to exploit Star Wars’ success, squeezed out other, mostly schlocky, sci-fi adventure projects, it never faltered. Disney fell into The Black Hole. United Artists’ floated Moonraker (James Bond in space). B-movie impresario Roger Corman’s Battle Beyond the Stars ripped off The Magnificent Seven. The TV pilots for Battlestar Galactica and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century first aired in movie theaters. …And, oh yeah, Star Trek came back!!!

Initially planned as a TV revival, Paramount’s beautiful-looking Star Trek: The Motion Picture earned points for excellent production values and getting the gang back together. Unfortunately, however, it failed to recapture the excitement of the original show. Plodding along at sub-impulse on a recycled story from the original series, once the introductions were over, the actors had little more to do than pose for reaction shots. Thankfully, Paramount did better at ripping themselves off on the ’82 sequel Wrath of Khan.

ONE LAST STRAY THOUGHT

Sadly, the years after Star Wars appeared were not kind to the Mego brand (World’s Greatest Superheroes). I’ll go into more detail later about my childhood love for Mego, but, for now, suffice to say that they passed on Star Wars. So, scrambling vainly to capture back market share in the wake of Kenner’s newfound dominance, Mego desperately committed to numerous expensive licensing agreements to sell space movie toys kids didn’t want. By 1983, they were bankrupt and out of business. (Pointing derisively) I think the words you’re looking for are “Haa Haa!”

Ok, that wasn’t very nice, but please forgive me. It was a shame to see Mego fold due to the unbelievable string of bad business decisions at the top. I loved those toys and lot of workers lost their livelihoods, but that’s how it usually goes, right? It makes me sad.